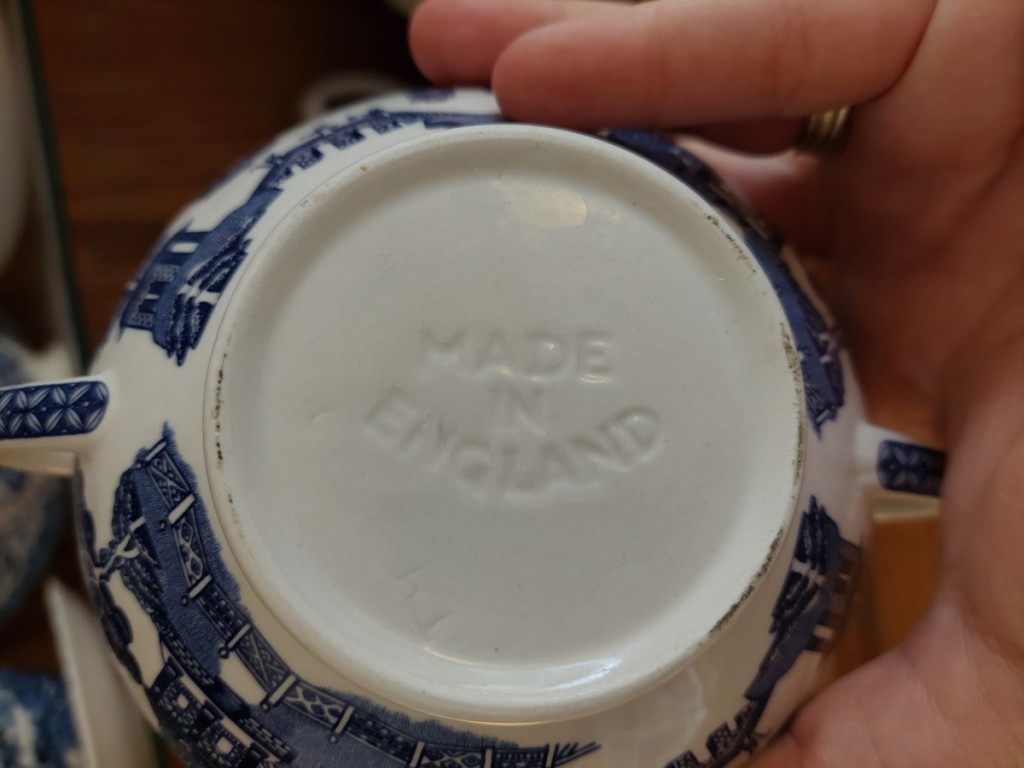

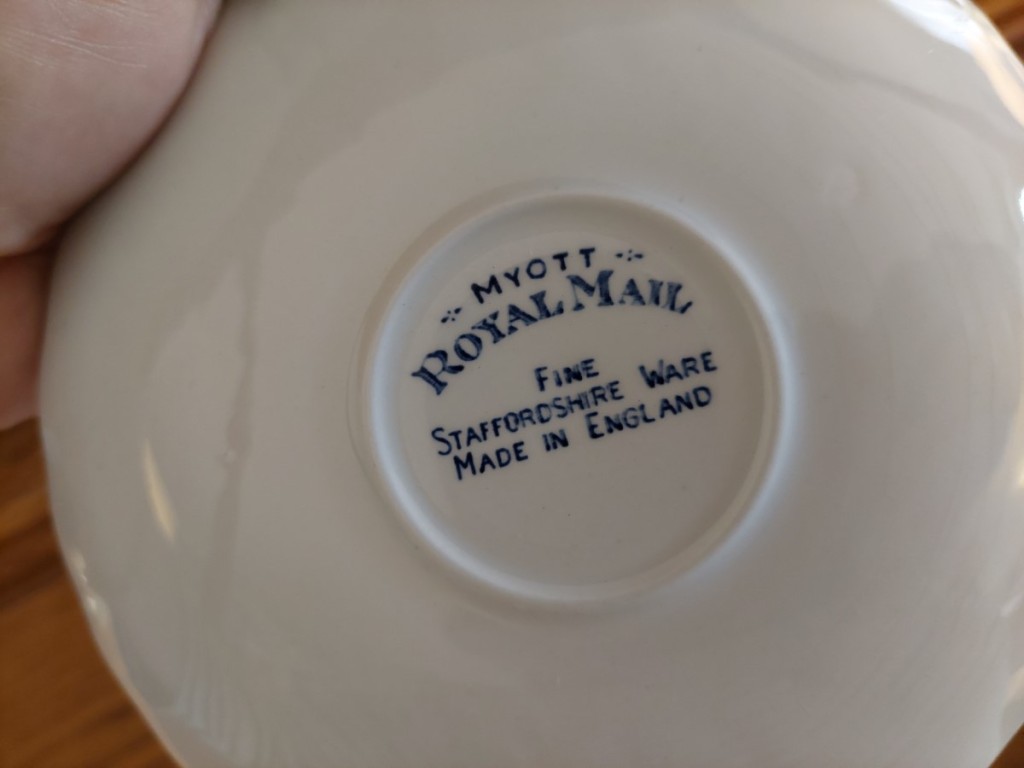

I hope you’ll forgive me for posting a blog entry that consists wholly of an essay written by someone else, but I’m about to start going on about blue transferware, and this seems a fitting introduction. Charles Lamb is a charming essayist and I was assigned to read this one when I was an English major.

~~~~~~

I have an almost feminine partiality for old china. When I go to see any great house, I inquire for the china-closet, and next for the picture gallery. I cannot defend the order of preference, but by saying, that we have all some taste or other, of too ancient a date to admit of our remembering distinctly that it was an acquired one. I can call to mind the first play, and the first exhibition, that I was taken to; but I am not conscious of a time when china jars and saucers were introduced into my imagination.

I had no repugnance then–why should I now have?–to those little, lawless, azure-tinctured grotesques, that under the notion of men and women, float about, uncircumscribed by any element, in that world before perspective–a china tea-cup.

I like to see my old friends–whom distance cannot diminish–figuring up in the air (so they appear to our optics), yet on terra firma still–for so we must in courtesy interpret that speck of deeper blue, which the decorous artist, to prevent absurdity, has made to spring up beneath their sandals.

I love the men with women’s faces, and the women, if possible, with still more womanish expressions.

Here is a young and courtly Mandarin, handing tea to a lady from a salver–two miles off. See how distance seems to set off respect! And here the same lady, or another–for likeness is identity on tea-cups–is stepping into a little fairy boat, moored on the hither side of this calm garden river, with a dainty mincing foot, which in a right angle of incidence (as angles go in our world) must infallibly land her in the midst of a flowery mead–a furlong off on the other side of the same strange stream!

Farther on–if far or near can be predicated of their world–see horses, trees, pagodas, dancing the hays.

Here–a cow and rabbit couchant, and co-extensive–so objects show, seen through the lucid atmosphere of fine Cathay.

I was pointing out to my cousin last evening, over our Hyson (which we are old fashioned enough to drink unmixed still of an afternoon) some of these speciosa miracula upon a set of extraordinary old blue china (a recent purchase) which we were now for the first time using; and could not help remarking, how favourable circumstances had been to us of late years, that we could afford to please the eye sometimes with trifles of this sort–when a passing sentiment seemed to over-shade the brows of my companion. I am quick at detecting these summer clouds in Bridget.

“I wish the good old times would come again,” she said, “when we were not quite so rich. I do not mean, that I want to be poor; but there was a middle state;”–so she was pleased to ramble on,–“in which I am sure we were a great deal happier. A purchase is but a purchase, now that you have money enough and to spare. Formerly it used to be a triumph. When we coveted a cheap luxury (and, O! how much ado I had to get you to consent in those times!) we were used to have a debate two or three days before, and to weigh the for and against, and think what we might spare it out of, and what saving we could hit upon, that should be an equivalent. A thing was worth buying then, when we felt the money that we paid for it.

“Do you remember the brown suit, which you made to hang upon you, till all your friends cried shame upon you, it grew so thread-bare–and all because of that folio Beaumont and Fletcher, which you dragged home late at night from Barker’s in Covent-garden? Do you remember how we eyed it for weeks before we could make up our minds to the purchase, and had not come to a determination till it was near ten o’clock of the Saturday night, when you set off from Islington, fearing you should be too late–and when the old bookseller with some grumbling opened his shop, and by the twinkling taper (for he was setting bedwards) lighted out the relic from his dusty treasures–and when you lugged it home, wishing it were twice as cumbersome–and when you presented it to me–and when we were exploring the perfectness of it (collating you called it)–and while I was repairing some of the loose leaves with paste, which your impatience would not suffer to be left till day-break–was there no pleasure in being a poor man? or can those neat black clothes which you wear now, and are so careful to keep brushed, since we have become rich and finical, give you half the honest vanity, with which you flaunted it about in that over-worn suit–your old corbeau–for four or five weeks longer than you should have done, to pacify your conscience for the mighty sum of fifteen–or sixteen shillings was it?–a great affair we thought it then–which you had lavished on the old folio. Now you can afford to buy any book that pleases you, but I do not see that you ever bring me home any nice old purchases now.

“When you come home with twenty apologies for laying out a less number of shillings upon that print after Lionardo, which we christened the ‘Lady Blanch;’ when you looked at the purchase, and thought of the money–and thought of the money, and looked again at the picture–was there no pleasure in being a poor man? Now, you have nothing to do but to walk into Colnaghi’s, and buy a wilderness of Lionardos. Yet do you?

“Then, do you remember our pleasant walks to Enfield, and Potter’s Bar, and Waltham, when we had a holyday–holydays, and all other fun, are gone, now we are rich–and the little hand-basket, in which I used to deposit our day’s fare of savory cold lamb and salad–and how you would pry about at noon-tide for some decent house, where we might go in, and produce our store–only paying for the ale that you must call for–and speculate upon the looks of the landlady, and whether she was likely to allow us a table-cloth–and wish for such another honest hostess, as Izaak Walton has described many a one on the pleasant banks of the Lea, when he went a fishing–and sometimes they would prove obliging enough, and sometimes they would look grudgingly upon us–but we had cheerful looks still for one another, and would eat our plain food savorily, scarcely grudging Piscator his Trout Hall? Now, when we go out a day’s pleasuring, which is seldom moreover, we ride part of the way–and go into a fine inn, and order the best of dinners, never debating the expense–which, after all, never has half the relish of those chance country snaps, when we were at the mercy of uncertain usage, and a precarious welcome.

“You are too proud to see a play anywhere now but in the pit. Do you remember where it was we used to sit, when we saw the battle of Hexham, and the surrender of Calais, and Bannister and Mrs. Bland in the Children in the Wood–when we squeezed out our shillings a–piece to sit three or four times in a season in the one-shilling gallery–where you felt all the time that you ought not to have brought me–and more strongly I felt obligation to you for having brought me–and the pleasure was the better for a little shame–and when the curtain drew up, what cared we for our place in the house, or what mattered it where we were sitting, when our thoughts were with Rosalind in Arden, or with Viola at the Court of Illyria? You used to say, that the gallery was the best place of all for enjoying a play socially–that the relish of such exhibitions must be in proportion to the infrequency of going–that the company we met there, not being in general readers of plays, were obliged to attend the more, and did attend, to what was going on, on the stage–because a word lost would have been a chasm, which it was impossible for them to fill up. With such reflections we consoled our pride then–and I appeal to you, whether, as a woman, I met generally with less attention and accommodation, than I have done since in more expensive situations in the house? The getting in indeed, and the crowding up those inconvenient staircases, was bad enough,–but there was still a law of civility to women recognised to quite as great an extent as we ever found in the other passages–and how a little difficulty overcome heightened the snug seat, and the play, afterwards! Now we can only pay our money, and walk in. You cannot see, you say, in the galleries now. I am sure we saw, and heard too, well enough then–but sight, and all, I think, is gone with our poverty.

“There was pleasure in eating strawberries, before they became quite common–in the first dish of peas, while they were yet dear–to have them for a nice supper, a treat. What treat can we have now? If we were to treat ourselves now–that is, to have dainties a little above our means, it would be selfish and wicked. It is the very little more that we allow ourselves beyond what the actual poor can get at, that makes what I call a treat–when two people living together, as we have done, now and then indulge themselves in a cheap luxury, which both like; while each apologises, and is willing to take both halves of the blame to his single share. I see no harm in people making much of themselves in that sense of the word. It may give them a hint how to make much of others. But now–what I mean by the word–we never do make much of ourselves. None but the poor can do it. I do not mean the veriest poor of all, but persons as we were, just above poverty.

“I know what you were going to say, that it is mighty pleasant at the end of the year to make all meet–and much ado we used to have every Thirty-first Night of December to account for our exceedings–many a long face did you make over your puzzled accounts, and in contriving to make it out how we had spent so much–or that we had not spent so much–or that it was impossible we should spend so much next year–and still we found our slender capital decreasing–but then, betwixt ways, and projects, and compromises of one sort or another, and talk of curtailing this charge, and doing without that for the future–and the hope that youth brings, and laughing spirits (in which you were never poor till now,) we pocketed up our loss, and in conclusion, with ‘lusty brimmers’ (as you used to quote it out of hearty cheerful Mr. Cotton, as you called him), we used to welcome in the ‘coming guest.’ Now we have no reckoning at all at the end of the old year–no flattering promises about the new year doing better for us.”

Bridget is so sparing of her speech on most occasions, that when she gets into a rhetorical vein, I am careful how I interrupt it. I could not help, however, smiling at the phantom of wealth which her dear imagination had conjured up out of a clear income of poor–hundred pounds a year. “It is true we were happier when we were poorer, but we were also younger, my cousin. I am afraid we must put up with the excess, for if we were to shake the superflux into the sea, we should not much mend ourselves. That we had much to struggle with, as we grew up together, we have reason to be most thankful. It strengthened, and knit our compact closer. We could never have been what we have been to each other, if we had always had the sufficiency which you now complain of. The resisting power–those natural dilations of the youthful spirit, which circumstances cannot straiten–with us are long since passed away. Competence to age is supplementary youth; a sorry supplement indeed, but I fear the best that is to be had. We must ride, where we formerly walked: live better, and lie softer–and shall be wise to do so–than we had means to do in those good old days you speak of. Yet could those days return–could you and I once more walk our thirty miles a-day–could Bannister and Mrs. Bland again be young, and you and I be young to see them–could the good old one shilling gallery days return–they are dreams, my cousin, now–but could you and I at this moment, instead of this quiet argument, by our well-carpeted fireside, sitting on this luxurious sofa–be once more struggling up those inconvenient stair-cases, pushed about, and squeezed, and elbowed by the poorest rabble of poor gallery scramblers–could I once more hear those anxious shrieks of yours–and the delicious Thank God, we are safe, which always followed when the topmost stair, conquered, let in the first light of the whole cheerful theatre down beneath us–I know not the fathom line that ever touched a descent so deep as I would be willing to bury more wealth in than Croesus had to purchase it. And now do just look at that merry little Chinese waiter holding an umbrella, big enough for a bed-tester, over the head of that pretty insipid half-Madona-ish chit of a lady in that very blue summer-house.”